When the editors of Penguin Random House went looking for someone to put a face to the thousands of refugees arriving in America, they knew who to turn to: Diya Abdo, Lincoln Financial Professor of English, whose parents are Palestinian refugees.

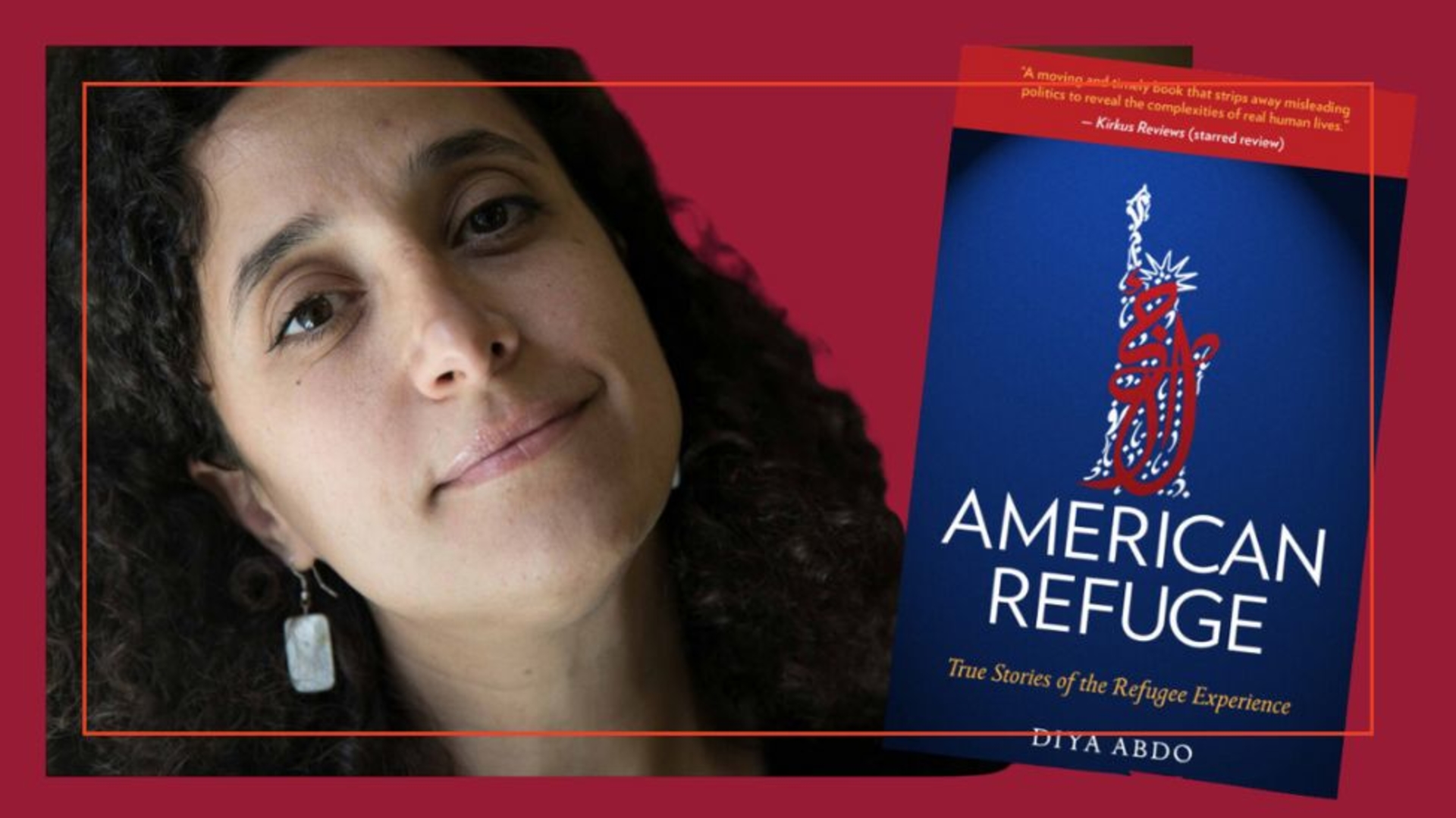

Caption: English Professor Diya Abdo will hold a book reading and signing at the Carnegie Room in Hege Academic Commons on Oct. 26.

She’s also the founder of Guilford College’s Every Campus A Refuge, which helps refugees transition into their new lives in Greensboro by leveraging available amenities and resources at the College. ECAR is a movement that has spread to other colleges and universities.

Diya’s new book, American Refuge, tells the stories of seven refugees’ experiences coming to America. Just as important, she tells the stories of the lives, homes, and families they left behind.

The College is hosting a book reading and signing at 4 p.m. on Wednesday, Oct. 26, in the Carnegie Room of Hege Academic Commons. We sat down with Diya to talk about her work with ECAR, the book and how she hopes the work can help the refugee issue in America.

Q: How did the idea of this book come about?

Diya: The publisher reached out to me because they have this particular series called truth to power. (The books) aim to tackle controversial subjects in ways that are grounded in narrative and not an argument, and they wanted someone to write a book about the refugee experience.

Q: Do you think that the topic has been framed too much by argument or debate rather than simply through telling their stories?

Diya: There are books that are being written about refugees and the refugee experience but this particular book is different because it captures the entire experience of someone who is seeking safety and security. It looks at the before times when the refugee was living at home in a place that they loved. It tells about the moment of rupture, the conflict that caused them to flee, and then life in a refugee camp. And then, you know, coming to the States, arriving here, resettlement, and then post-resettlement, but all of that is told through story. What's unique about this book is that in the media, generally, we've been debating and arguing about refugees and who they are, what they are. There are lots of myths about refugees that have been perpetuated by various actors. This book really aims to bust those myths through story.

Q: You come from a refugee family yourself. What perspective role did your own family history play in the writing of this book?

Diya: So I was born to refugee parents, and they were displaced in Jordan. I think the role that they played, for me, gave me a deep understanding of the refugee experience and what it meant to be someone who was displaced. As a refugee you might have found safety and security but that doesn't mean that you necessarily have found home or belonging or inclusion or even integration. And this was in a country that was very similar to the country that they left, people who spoke the same language and ate similar food. So how about when people come to a country where they're speaking a different language, and it's so geographically different and so far away? For me, it was just a keen understanding, an investment of what it meant to be out of place.

Q: There’s a lot of misinformation or myths about refugees. What are some you wanted to set the record straight on?

Diya: One of them is that refugees leave shit-hole countries, which is not true. They leave countries they love, very beautiful countries where they were very happy. Another myth is that refugees choose to leave. That is not true. Refugees are refugees. It's a very particular status. They leave because they're forced to leave. Another myth is that refugees are not well-vetted. We heard this a lot, especially under the Trump administration. Refugees undergo extensive and exhaustive processes of interrogation and questioning and interviewing by various agencies. Another myth is that refugees resettled, also not true. Ninety-nine percent of refugees will never be settled. There's 26 million refugees in the world and 85 million are displaced. Actually there’s more now because of (the war in) Ukraine. Most refugees live in refugee camps for the rest of their lives and their children's lives and their grandchildren's lives. Another myth is that refugees receive a lot of resources when they come to the United States. Refugees receive a one-time stipend of $1,000. They have to pay back the plane ticket that brought them here. And they're expected to become self-sufficient within 90 days. And another myth is that refugees should be happy when they get here because it's, you know, sort of the Holy Grail. In fact, a lot of refugees are really lonely and homesick. And so the resettlement experience might be a safe one, but it's not always necessarily one of belonging and inclusion.

Q: What do you hope people get out of this book?

Diya: There are a lot of statistics and data out there about numbers and conflict, images of people fleeing and dying as they're trying to cross borders and reach safety. I wanted these stories to be grounded in dignity because often we speak about refugees really as either objects of pity or fear. I wanted a book that really grounded the stories in the personal, in the individual, in dignity and agency. My hope is that if people who might know about one piece of the refugee experience, might get to know a more whole picture. And if they don't know anything, then this book is a really great foray into just general knowledge about the refugee experience.